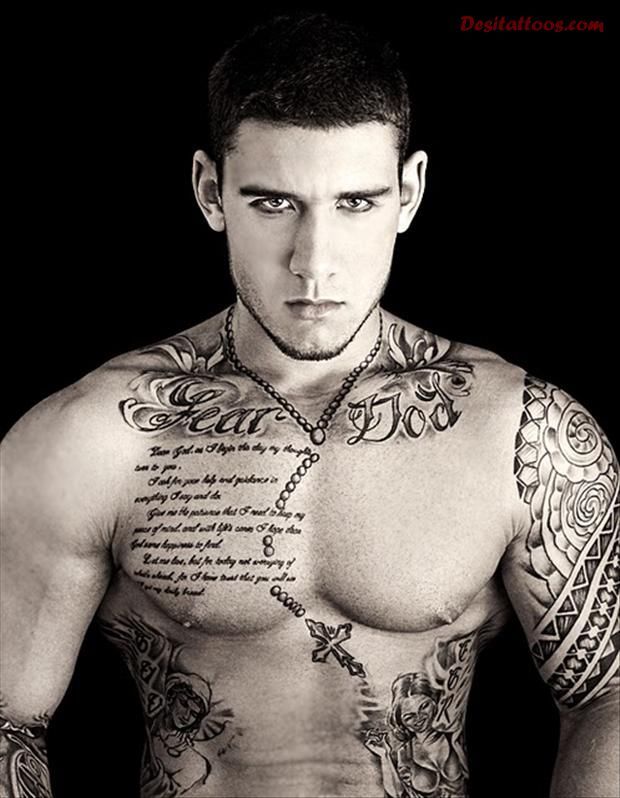

I try to keep this blog focused on liberal education, but here's something different: SKIN: A Probe into Greek Ways of Thinking DRAFT: Criticisms and suggestions welcome [email protected] This draft essay is part of the Thinking Greek project –an attempt to bring into sharper focus the distinctive nature of thought among the ancient Greeks –not , for a change, the great ideas, philosophical insights, or attainments of the intellectuals, but how ordinary Greek citizens went about making decisions, and figuring out how to cope with the world around them. One underlying premise of the project is that abstract categories, such as beauty, truth, were slow to develop and gain traction. Most people, most of the time, I hypothesize, thought through analogues and metaphors drawn from the natural world, not least the human body. Skin, then, may be a useful staring point. Bob Connor June 2015 -- χροῒ δῆλα Skin makes things clear. Pherecydes of Syros (cited in Diogenes Laertius Lives of the Eminent Philosophers I 118) At a do or die moment for Greek mercenaries trapped in the middle of Anatolia and facing possible extinction from Persian forces attention turned to an ear lobe. Had Apollonides’ ears been pierced? The issue was not a suspicion of effeminacy but doubts about Apollonides’ Greekness, even though he had a good Greek name and spoke a well-known Greek dialect. Xenophon, rejecting Apollonides’ contention that ”anyone who said he could gain safety in any other way than by winning the King's consent through persuasion, if possible, was talking nonsense “ (Xenophon Anabasis 3.1, 27). Xenophon interrupted him, refuted his arguments, and urged his fellow commanders to remove Apollonides from their councils. Then Agasias, one of those commanders, went a step further, breaking in and saying, “For that matter, this fellow has nothing to do either with Boeotia or with Greece at allt all, for I have noticed that he has both his ears bored, like a Lydian's.” (3.1.30) That did it. Apollonides was out and so was any attempt to conciliate the Great King; the Greks would fight their way home if anyone tried to stop them. Detail of Attic red-figure amphora, ascribed to Myson, in the Louvre (1836 G 197), showing Croesus, the Lydian king, with an ear-ring. That is a minor episode, but revealing about the taboo against skin piercing among the Greeks. In many cultures skin has magical powers, and needs to be treated with great respect; but often that is accompanied with piercing, curing or scarification rituals. But not among free Greek males. Attitudes toward the tattoo remind s of that fact. Greeks might brand or tattoo their slaves, but with one notable exception (Epimenides of Crete; separate discussion forthcoming) we know of no free Greek who was tattooed. Egyptians tattooed; so did Scythians, but never free Greeks. Greeks also avoided circumcision, even though it was practiced by many people inn the ancient world. After Alexander’s conquests in the Near East there were powerful economic and cultural reasons to Hellenize, and that meant avoiding circumcision. Those forces were at work even among the Jews in Jerusalem in the second century before our era: In those days lawless men came forth from Israel. And misled many, saying, “Let us go an make a covenant with the Gentiles round about us for since we separated from them many evils have come upon us.” This proposal pleased them, and some of the people eagerly went to the king. He authorized them to observe the ordinances of the Gentiles. So they built a gymnasium in Jerusalem, according to Gentile custom, and removed the marks of circumcision, the holy covenant. 1 Maccabees 1 vs. 11 – 15 (RSV) The situation in Jerusalem is described with further detail in 2 Maccabees ch. 4 , where the responsibility for the Hellenizing movement is [;aced on the high priest, Jason, who “at once shifted his countrymen over to the Greek way of life” ( 2 Maccabees 4.10 ) including the building of a gymnasium. The account goes on to describes the priests hastening “to take part in the unlawful proceedings in the wrestling arena after the call to the discus,” (v.14) and the quadrennial games at Tyre (vs. 18). In short, Jerusalem Hellenized; it became a Greek polis, in which, of course, there was a gymnasium, and there circumcision would be evident. It was a sign one had not really Hellenized. Skin, then, provided a negative but powerful way of defining Greekness. Being Greek meant avoiding certain practices that were well known in the ancient Mediterranean world. It also, encoded gender differences among the Greeks: women could have their ears pierced, but not men Skin coloration, moreover, encoded socissl oles, to judge from some Attic vase painters who represented females with white skin, as if they never stepped out of the dark inner recesses of the Greek house, and males with dark skin, as well tanned outdoorsmen. Skin also, however, seems to have provided a boundary on seeking certain kinds of knowledge seeking. Heinrich von Staden has shown in a brilliant article the cultural context within which the dissection of human beings was long avoided, then flourished briefly in Alexandria in the third century before our era, when Herophilus and Erasistratus conducted autopsies, and then disappeared untilthe fourteenth century. Marsyas: The norms that were reflected in Greek attitudes toward the piercing or cutting of human skin could be inverted in myth. Greeks retold the story, probably originally tied to an ancient Near Eastern mourning ritual, of a competition between Apollo, the divinity who embodied many Greek ideas of manliness, and a contentious Silenus figure named Marsyas. The story is localized near the river Marsyas in Phrygia, that is, in a region imagined as a virtual anti-Greece. There the Great Mother, Cybele, dominated religious life, along with her consort Attis, and castrated priests, the Galli. There Marsyas used his aulos (a reed-based instrument closer to a recorder than to a flute) to challenge the divinity whose favorite musical instrument was the cithara, the antecedent of the modern guitar. Apollo was not satisfied with the victory accorded to him by a friendly jury of Muses; the presumptuousness of the Marsyas in challenging an Olympian divinity had to be punished. So Apollo stripped the skin off him while he was still alive, treating a human-like creature more brutally than an animal flayed after slaughter. Marsyas’ hide, it was said, was then hung up for all to see in the market place of Celaenae (Herodotus 7.26.3). The Marsyas myth, as Greek and Roman authors tell it, turns upside down several antitheses that often recur in Greek thought –the contrast between human and divine, the frenzied music of the aulos vs. the Apollonian restraint of the cithara, and skin vs. hide. The myth carries with it a warning about over stepping boundaries The Greek language, like English, distinguishes the skin of a human (ho chros, he chroiao, ) from the hide of an animal (derma). In Greek the linguistic distinction corresponds to a difference in practice. To kill and animal, strip its hide, tan it, use it as leather (diphtheria) posed no problem for the Greeks. But to do the same to a human would be an abomination. This distinction between animal and human leads into fresh territory, for in the Geek imagination that distinction is permeable. Men, particularly in moments of sexual excitement, are imagined to have goat hooves and tails; they become satyrs. Man and bull are fused in the ferocious Minotaur; centaurs, half human half horse, seize women and fight off the fully human Lapiths. Just as the divide between animal and human is crossed by these imaginary creatures, the skin too is not an insuperable separation. The ancient Greeks seem to have been well aware that the skin had many passageways, poroi, pores, through it. It was not a protective sheath around the body, but permeable, quite literally porous. (See LSJ s.v. πόρος I 6). Like other openings in the body the skin provides, in effect, means for inflow and outflow. That notion is especially important given Greek attitudes toward the inspiration and the emotions, both of which are often conceived of as flows from the outside into the body. Eros, for example, is often imagined as originating through vision, but in concrete terms, through the eyes. [Separate discussion forthcoming]. In addition, the process of inspiration was sometimes imagined as an infusion through openings in the body. Origen, in the third century of our era, criticized the idea that the inspiration of the Pythia might be understood as sexual possession by Apollo: It is said of the Pythian priestess, whose oracle seems to have been the most celebrated, that when she sat down at the mouth of the Castalian cave, the prophetic Spirit of Apollo entered her private parts; and when she was filled with it, she gave utterance to responses which are regarded with awe as divine truths. Judge by this whether that spirit does not show its profane and impure nature, by choosing to enter the soul of the prophetess not through the more becoming medium of the bodily pores which are both open and invisible, but by means of what no modest man would ever see or speak of. Origen Against Celsus 7.3 Origen does not reject the idea that Apollo has inspired hisproestess; he simply substitute other openings in the body for the idea of sexual penetration. Conclusion: Skin is a boundary marker and as such a locus for anxiety. That ca be seen in the treatment of the skin in many cultures. But cultures and sub-cultures differ widely in the ways the ski is treated and conceptualized -- the three images at the head of this essay are there to remind us of just that point. Among the ancient Greeks the anxiety associated with skin may have been comparatively high, since it was used in that culture to mark important contrasts, Greek v. non-Greek, male vs female, animal vs. human, inner vs outer. Yet the Greeks observed strict restraints on any form of bodily penetration or cutting. That may in part result from the vulnerability of the body in a culture where war was recurrent and fought out spear, javelin and arrow. But the restraint may also have a metaphorical significance, reflecting the perceived permeability of the very contrasts and categories embodies in the metaphorical significance of skin in that culture. It is not surprising, then, to find among the Greeks a reluctance to cut, pierce or in any way weaken the skin. Some Reading: E. Fernandes “Disease” in N. Wilson, ed. Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece, pp. 233 –34. Mark Johnson, The Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination, and Reason (Chicago, Univ. of Chicago Press 1987) Adrienne Mayor, “People Illustrated” Archaeology March / April 1999 pp. 54 -57. PDF Heinrich von Staden, “The Discovery of the Body: Human Dissection and Its Cultural Contexts in Ancient Greece“ Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 65 (1992) pp. 223-41 S. Tougher, “Eunuchs” in Nigel Wilson, ed., Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece ( ) pp. 280- 81. . |

|

2 Comments

Robert Sutton

6/22/2015 04:44:46 pm

Bob,

Reply

W. Robert Connor

7/9/2015 02:59:29 am

Bob-- Thank you so much for these learned and very helpful comments. If I revise the piece for puyblication, I will surely incorporate them.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed